STOP FOOD WASTE

What do ‘best before’ dates on food really mean?

The question:

What do “best before” dates on food packages mean? Is it safe to eat foods after these dates expire? Are they still nutritious?

The answer:

Once you open a food, the best before date is no longer valid. For opened packages, manufacturers are required to provide storage instructions on the label when they differ from normal room temperature – for example, “refrigerate after opening” or “keep refrigerated.”

If you store foods properly, many fresh foods like eggs, milk and yogurt can be safely eaten soon after their best before dates have expired. Many packaged foods such as crackers, cookies, canned soup and tinned tuna can be eaten safely well long after the best before date. That doesn’t mean these foods will taste as fresh, however. They may have lost some of their flavour and their texture may have changed. Think of best before dates as suggestions about how long food will retain its freshness.

Although canned and packaged foods have a much longer shelf life than fresh foods, keep in mind they can lose anywhere from 5 to 20 per cent of their nutritional content every year. Be sure to store canned foods in a cool, dry, dark cupboard.

“Packaged on” dates are different than best before dates. Mandatory for meat and poultry, these dates tell you the day the fresh food was packaged in the store. The “packaged on date” is usually the starting point for how long you can expect the food to stay safe to eat.

“People have eaten a can of food 40 years later and been okay.”

— Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic

These are supermarkets that specialize in items that other chains no longer want to sell –such as discontinued, overbuys, or items near or even past the expiration date.

While these stores aren’t for everyone, they do attract price-conscious shoppers looking for deals. And the deals can be significant. One example: a box of cereal that sells at most regular grocery stores for nearly $5.00 can cost as low as $1.00

Food Waste: The Issue of Food Waste

Food Waste by the Numbers

$31 billion worth of food is wasted in Canada each year.[i] This is approximately 40% of food produced yearly in Canada

Households in Canada on average waste $28 worth of food each week ($1456 annually)[v]

The accumulative cost of associated wastes (i.e. energy, water, land, labour, capital investment, infrastructure, machinery, transport) has been estimated by the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organization at 2.5 times greater than the “face value” of wasted food, making the overall cost of food waste in Canada exceed 100 billion[ii]

Land filled organic matter creates methane gas which is 25x more damaging to the environment than carbon dioxide[iii]

According to Statistics Canada, in 2007 Canadians wasted the equivalent of 183 kilograms of solid food per person between retail level and the plate, amounting to over six million tonnes

Approximately 47% of food wasted in Canada occurs at home. The other 53% of wasted food is generated along the value chain when food is produced, processed, transported, sold, and prepared and served in commercial and institutional settings[iv]

Approximately 80% of consumer food waste was once perfectly edible[vii]

Food waste was highlighted in the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario’s Annual Report (2011/2012) as an emerging issue that may be escaping broader public attention and has the potential for significant environmental impacts.

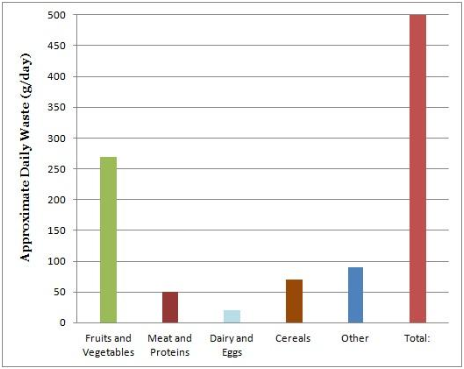

An Average Household’s Food Waste in a medium sized Ontario Municipality

(Massow and Martin, n.d.)

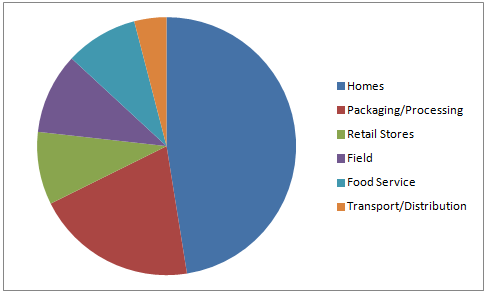

Percentage of Food Waste Throughout the Chain (field to home) in Canada

(Gooch et al, 2014)

Hierarchy of Food Recovery

Food waste reduction and diversion initiatives take a variety of approaches that can be prioritized through food recovery pyramids. These initiatives focus on both edible and inedible food waste.

Prevention: Avoid the Generation of Food Waste

Re-use: Feed People in Need

Recycle: Feed Livestock Food unfit for Human Consumption and/or Compost Food Waste

Recovery: Produce Renewable Energy with Unavoidable Food Waste

Disposal (Landfill/Incineration)

Food Waste and Toronto

- The Green Lane Landfill cost Toronto approximately ¼ billion dollars.

- In 2013 the City of Toronto reported approximately 111,848 tonnes of residential organic waste were diverted from landfill through the Green Bin Program. This makes up 25% of all residential diverted waste[viii]

Toronto’s Long Term Waste Management Strategy

As the City of Toronto develops its Long Term Waste Management Strategy the TFPC has been working towards strategically including food waste as a priority in the Strategy.

Potential benefits for the City of Toronto include:

- Reduce the amount of organic waste in the waste stream

- Reduce greenhouse gas landfill emissions including the amount of methane gas created by landfilled organic matter and biogas created at source separation facilities

- Generate increased public interest in the benefits of waste management

- Turn the City of Toronto into a leader on the emerging issue of food waste reduction and diversion